Divide-And-Conquer

Information on this page is taken from The Algorithm Design Manual by Steven S. Skiena.

One of the most powerful techniques for solving problems is to break them down into smaller, more easily solved pieces. A recursive algorithm starts to become apparent when we break the problem into smaller instances of the same type of problem. Divide-and-conquer splits the problem in (say) halves, solves each half, then stitches the pieces back together to form a full solution. Whenever the merging takes less time than recursively solving the two subproblems, we get an efficient algorithm. For example, mergesort takes linear time to merge two sorted lists of \(n/2\) elements, each of which was obtained in \(O(n \lg n)\) time.

Recurrence Relations

Many divide-and-conquer algorithms have time complexities that are naturally modeled by recurrence relations. A recurrence relation is an equation that is defined in terms of itself. The Fibonacci numbers are described by the recurrence relation \(F_n = F_{n - 1} + F_{n - 2}\). Many other natural functions are easily expressed as recurrences. For example, \(a_n = 2a_{n - 1}, a_1 = 1 \rightarrow a_n = 2^{n - 1}\).

Divide-and-conquer algorithms tend to break a given problem into some number of smaller pieces (say \(a\)), each of which is of size \(n/b\). Further, they spend \(f(n)\) time to combine these subproblem solutions into a complete result. Let \(T(n)\) denote the worst-case time the algorithm takes to solve a problem of size \(n\). Then \(T(n)\) is given by the following recurrence relation.

\begin{equation} T(n) = aT(n/b) + f(n) \end{equation}For example, the running time behavior of mergesort is governed the recurrence \(T(n) = 2T(n/2) + O(n)\). This recurrence evaluates to \(T(n) = O(n \lg n)\). Binary search is governed by the recurrence \(T(n) = T(n/2) + O(1)\).

Example

This example comes from Elements of Programming Interviews by Aziz et al.

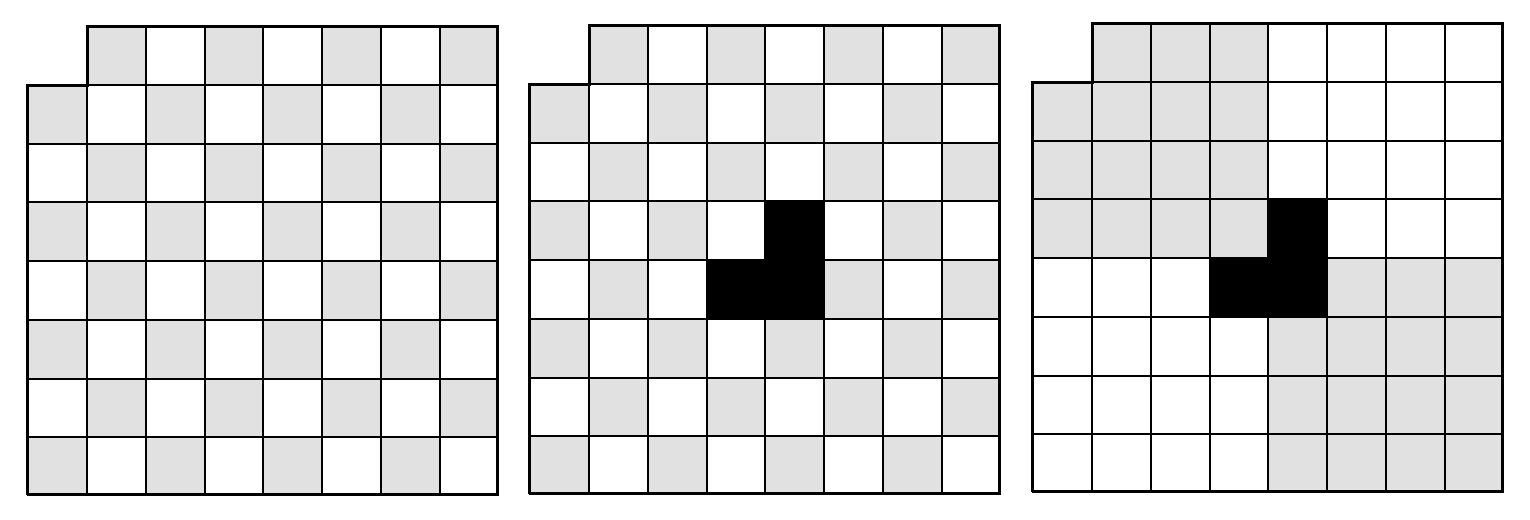

Suppose we are asked to design an algorithm that computes a placement of 21 triominoes that covers the 8x8 Mboard. A triomino is three unit-sized squares in an L-shape. An Mboard is a mutilated chessboard made up of 64 unit-sized squares arranged in an 8x8 square, minus the top-left square.

The key insight is that if a placement exists for an \(n\) x \(n\) Mboard, then one also exists for a \(2n\) x \(2n\) Mboard. Now we can apply divide-and-conquer. Take four \(n\) x \(n\) Mboards and arrange them to form a \(2n\) x \(2n\) Mboard square in such a way that three of the Mboards have their missing square set towards the center and one Mboard has its missing square outward to coincide with the missing corner of a \(2n\) x \(2n\) Mboard. The gap in the center can be covered with a triomino and, by hypothesis, we can cover the four \(n\) x \(n\) Mboards with triominoes as well.

With divide-and-conquer, the algorithm works by repeatedly decomposing a problem into two or more smaller independent subproblems of the same kind, until it gets to instances that are simple enough to be solved directly. The solutions to the subproblem are then combined to give a solution to the original problem.